The Tricky Business of Business

April 2, 2024

Recently, the New York Times published an article that carried the headline, ‘Boeing Faces Tricky Balance Between Safety and Financial Performance.’

Duh.

All high-hazard businesses face that tricky balance.

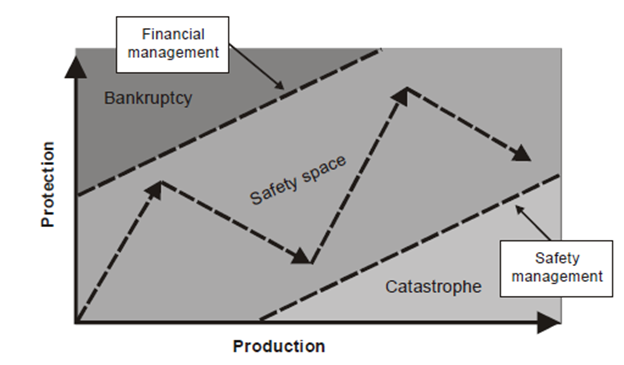

In fact, the International Civil Aviation Organization’s Safety Management Manual references Dr. James Reason’s work on this subject, presenting the following graphic:

Companies endeavor to increase production, expand markets and gain market share.

In doing so, they navigate the company along a trajectory… like driving a car down a road. There are two ditches, one on either side… One is financial ruin, the other is catastrophe.

Financial ruin could be bankruptcy, involuntary downsizing, breakup, loss of assets, acquisition by a competitor for pennies on the dollar. It could be loss of license to operate.

Catastrophe is a safety event involving loss of assets, injury or death, environmental impact, regulatory and liability penalties… all of which can create financial disaster as well.

We steer along our path between these ditches, but we seldom do it in a straight line.

We typically change course as we approach a ditch… too far toward financial ruin, and we cut spending… often focusing on cutting things we don’t see as immediately important to our work.

We cut costs until we get to a place where we get scared of a safety event… we have a near miss, an incident or a regulatory finding. Then we start spending more on safety and move away from that ditch…. Which takes us closer to the other ditch.

Now, if we take the idea of driving a car on a road a bit further, we see a problem with this analogy… in a car, we have one driver, and to be an effective driver, he or she has to focus on the road, not the ditches.

But that’s not how it works in many, maybe most companies.

There’s a team working the business of the company… in oil and gas, we might describe this as finding and producing hydrocarbons, transporting them, refining them, transporting again and marketing to consumers. They do their work to create value, to build a buffer between the business and the financial ruin ditch.

Meanwhile, a different team is watching the catastrophe ditch… they audit, monitor, investigate and recommend actions to reduce risk.

But, these recommendations are implemented by the folks doing the business of the company (the people watching the financial ruin ditch)… and they prioritize what gets done based on their acceptance of the recommendations from the team watching the catastrophe ditch.

And therein lies a challenge. The people who have the levers to actually fix safety issues are usually the ones minding the financial ruin ditch… and their metrics of success are things like schedule, production, and cost. And if they do have safety metrics, they are usually lagging indicators… things like lost workdays, reportable injury frequency, LOPCs, etc. Things that have already happened.

A lot gets lost in translation between the two groups.

Sometimes, a perception emerges that places operational risk control squarely opposite productivity. I have a couple of quotes from some high-hazard industry leaders that illustrate this.

One is from an engineering manager, interviewed after an accident. His team was aware of a defect in a critical system and had an opportunity to intervene and delay the operation, but there was an aggressive schedule to meet.

Here’s the quote: ‘Safety is like caviar…. A little on a cracker is fine, but you can’t eat a whole pound of it in one sitting.’

The engineering manager involved was employed by NASA; the accident in question was the explosion of the space shuttle Challenger during launch.

More recently, a CEO of a small maritime company said, ‘You know, at some point, safety is just pure waste. …’

That second quote is from an interview with the late Stockton Rush, CEO of OceanGate and commander of the Titan submersible which imploded while exploring the wreckage of the Titanic.

I agree, these are extreme statements, made even more so by the gift of hindsight, but they are indicative of widely held perception that operations and safety management compete. In fact, they don’t have to.

Consider the analogy presented about driving down a road between the two ditches. A competent driver concentrates on the roadway, maintaining position, controlling speed appropriately. By doing so, the driver tracks toward the destination and by virtue of staying on the road, avoids the ditches. So should a competent company steer on the desired path toward its destinations of profit, return on investment, growth and market share.

The key is to define the path… unlike travelling on a road, we don’t have a pre-determined path to follow in a competitive commercial enterprise. That is what strategy is all about… divining a path where none exists. What we do know is that there are limits to the path… that there will be ditches present on either side. Knowing these boundaries helps us define a good path, and if people across the organization understand and embrace that path, we can dampen the zig-zag between the ditches and make our travel toward our business performance destinations (targets) more efficient and reliable.

So, back to the NYT article. Yes, Boeing faces a tricky challenge balancing safety and financial success. My take on their situation is that they have been tacking over to the ‘catastrophe’ side of the safety space while patting themselves on the back for making good profits. They will (either voluntarily or involuntarily) take action to steer back toward center, but, like most companies, indeed, most humans, they will experience a few years of relative calm on the safety front, which will make their safety efforts seem draconian, then cut costs until they bump into the ‘catastrophe’ ditch again.

What I’m not sure of is whether they actually have a strategy that speaks to how they do business. With the Boeing-Airbus duopoly in the world-wide commercial airliner sector, Boeing has become more reactive than proactive, I believe. If they had a strategy (a defined path toward success), they appear to side-step that strategy to make poorly considered decisions in reaction to their competitor. I’m working on another blog entry to discuss this in more detail.

In conclusion, let me offer another analogy. In sailing, a critical part of performance is choosing the right course and then balancing the boat… adjusting sail trim to control heel to keep the hull efficient, reduce rudder deflection required to hold the desired heading, and maximize the sails’ ability to extract energy from the wind. One cannot sail on all points of wind… there are ‘ditches’ we have to avoid. Sometimes that means we can’t go directly where we want to, but if we plan and develop a strategy, we can tack the boat and make progress upwind, or gybe and make progress downwind.

It’s a skill that is never perfected, but rather constantly honed.

I would suggest that high-hazard endeavors have the same challenge, to define and then steer efficiently along the desired trajectory… to stay between the ditches, back to the road analogy.

Yes, Boeing is facing a tricky balance between safety and financial performance.

Don’t we all.

Some thoughts on learning

January 18, 2024

In aviation training, a lot of effort is made around how to instruct. In fact, one of the hardest written tests I have taken is the Fundamentals of Instructing (FOI) required for flight and ground instructor certification. I thought it was hard because it was outside the mainstream pilot knowledge areas (like regulations, performance, weather, navigation and so on). It was actually not so difficult in that the questions were taken directly from the FAA’s Aviation Instructor Handbook… a book I read but did not fully understand until I started teaching.

Once I started teaching, it became obvious to me that while there was a lot of guidance on how to teach, students had no such guidance on how to learn. With time, I started sharing some pointers on how to learn the pilot craft, and understanding some of the concepts helped me immensely in my own training experiences, especially advanced training such as additional category or class ratings and type ratings.

Here are some of my recommendations for any student:

Think of aircraft systems from the perspective of ‘flow.’ All systems have a flow from a source to the final user. For example, fuel systems flow from the fuel filler port, through the tank, the fuel pickup, valves, pumps, heaters, fuel control units and finally the fuel nozzles. Flight control flows from the pilot stick/wheel/rudder through cables, pushrods, actuators, potentiometers, automated flight control systems, autopilots, trim systems, and ultimately to a control surface that deflects as directed. All systems involve a source point and a final user…. and lots of stuff in between.

Understanding the flow helps you understand what the system does in normal operation. You can then ask yourself, ‘What happens if X fails?’ If you know the flow, you can understand what impact that failure has. Knowing the flow will help you understand limitations, pre-flight inspection items, pre-takeoff checks and abnormal and emergency procedures better. It will make the ‘knock-on’ effects of component failures more obvious and help your judgement and decision-making.

Flight procedures and profiles can be simulated without a simulator. I added a multiengine sea rating back in the early 1980s. The airplane, a Republic Seabee converted to the UC-1 Twin Bee, was about $225/hour with the instructor. For a young flight instructor that was a big deal, and my buddy and I did everything we could to reduce our training time.

In our hotel room, we set up two chairs to represent the cockpit seats… we placed empty soft drink bottles on the floor to replicate the gear and flap levers. We went through every normal abnormal and emergency procedure and each of the flight test operations (stalls, Vmc demonstration, etc.) in our very basic cockpit procedure trainer. We probably saved between 3 and 5 hours of flight time by nailing down the procedures in the hotel room.

In the 1990s, I attended Falcon 50 type rating training at SimuFlite. Given the variables of normal (three engine), one engine inop, two engine inop, with/without flaps/slats, precision and non precision approach, there are a lot of potential flight profiles for approach and landing.

I set up a coffee table in my hotel room as the runway and literally walked around the room, taking off, departing the terminal area, arriving in the terminal area, maneuvering onto final and flying the approach to the runway. I made up flashcards outlining each of the profiles, and holding them in my hand, I walked through the procedures. I called out flap, gear, airspeed, and approximate N1 setting at each key point, ran through the checklist and made the approach callouts. If someone was watching, they may have thought I was crazy…

Learn one aircraft very well… the rest will be easier to understand. I was a flight instructor at FlightSafety International in the 1980s, training pilots on the Turbo Commander and Jetprop Commander series of airplanes. I taught all phases…. ground school, simulator training and in-flight training, both initial and recurrent courses. Teaching the ground school courses was challenging… it was like taking a 30 hour oral examination on the airplane.

But, that experience let me learn one aircraft very well, and subsequent aircraft were easier to learn. The fundamentals learned well in one aircraft supported understanding even dramatically different airframes. I could leverage the similarities, certainly, but I found I could use the differences as well to better understand the system, and the procedures and techniques.

Learn one way well, then look at different techniques. I had two poor learning experiences in my flight training. One was in the instrument helicopter course I took at FlightSafety International. We were using the Bell BH-222, a very capable IFR helicopter. The 222 can be flown manually, with flight director and stability augmentation, or on autopilot. I had a different instructor for each of my first few simulator sessions…. each had a different philosophy on flying on instruments. One wanted me to fly with stability augmentation and using the flight director, the next using raw data and force trim, the one after that using autopilot. I finally had to say, ‘I just want to learn one way well… then we can look at the other methods.’

At the Falcon 50 initial course at SimuFlite, I was paired with an experienced pilot on type. The instructor was training the school profiles for procedures, and doing a good job, but my ‘stick buddy’ kept interjecting how he would do it. Basically, I had two instructors simultaneously, and they did not share the same lesson plan. I finally had to tell my cohort that, while I appreciated his input, one instructor was enough, and only the SimuFlite guy was on the payroll. Now, this had a bit of a negative impact, as he shut up for the next session, not even doing his pilot-monitoring role. So, we had to have another chat to get him re-engaged.

There’s a difference between procedure and technique. In my work at FlightSafety, I instructed experienced, qualified pilots transitioning to a new type of aircraft. Each brought their experience and training to the fray, and the variety of piloting techniques was wide. Take crosswind landing, for example. Some transitioned from the crab to the slip during the flare, others made the transition higher, sometimes as high as 100 feet above touchdown. It didn’t matter, as long as they knew how to crab and how to slip, and had a plan to make the transition before landing, with the airplane aligned with the runway, with zero drift at the time of touchdown. That was technique.

Procedure is less flexible. The steps required to deal with an engine failure after liftoff, or a rapid decompression at altitude, or an electrical fault on a DC bus are procedures… step one, step two, step three… Sure, there is some technique involved, but the success or failure of the event is primarily related to adherence to the procedure.

Know the procedures early on. Learn the techniques over your entire career.

Optimism

January 19, 2024

Individuals, organizations and industries all suffer from a common fault... we are notoriously optimistic.

That's a good thing.

Being optimistic has allowed us to do amazing things... explore new lands, transit oceans, fly in the sky, even leave our planet home. When risks are revealed, we tend to think more of the opportunity, not the liability.

When the risks come to fruition, we sometimes see that as a significant emotional event.

Take speeding as an example. Nearly all of us do it, and nearly all of us can enumerate the risks: increased potential for an accident, issuance of a speeding citation and fine, increased insurance cost, even loss of license in the extreme.

Yet, we all do it.

The day we get a speeding ticket, we usually start following the rules.... after all, we don't want a second ticket and higher fines, higher insurance, etc. We follow the rules until we get comfortable with our old habits, and sure enough, our speed creeps up.

Pretty soon, we're back to our normalized speeding behavior.

How we talk about these significant emotional events says a lot.

I once heard a co-worker at BP tell me 'We've finally gotten Deepwater Horizon behind us.' Even though it had been several years after the accident and much progress had been made by the company, to me, it was a disturbing comment.

Why? Because for any individual, any company, any organization or any industry, the significant emotional events are not just behind us... they are in front of us as well.

For aviation, TWA 800 and Tenerife are ahead of us.

For the oil and gas industry, Piper Alpha and Deepwater Horizon are ahead of us.

For the electric grid industry, the Camp Fire is ahead of us.

Whatever the watershed event is for your industry, it is ahead of you.

We just don't know it's new name.

Yet.

The trick is to learn its name before it becomes a reality.

Like the Ted Lasso quote of Walt Whitman, 'Be curious, not judgmental.'